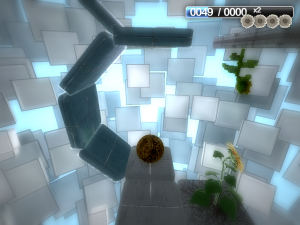

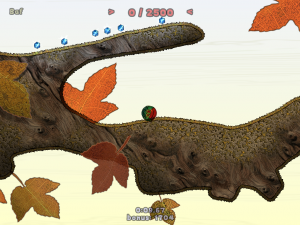

Puzzle Dimension: Clusters and Tiles

Like many games, Puzzle Dimension introduces new game elements one by one over the course of play. Except it kind of introduces them in pairs. The levels are grouped into “clusters” of ten, and all of the earlier clusters introduce two elements. If you play the levels within a cluster in order, you get the new elements one at a time, but you don’t have to play them in order; unlocking a cluster makes all of its levels available.

Most of the clusters have titles that play on the things they introduce — for example, the first cluster, “Broken Ice”, introduces first breakable tiles, which crumble after one use, and then ice tiles, which force you to keep moving in a straight line. It’s a pairing with a great deal of puzzle potential, as the ice tiles make it important which direction you move onto them from and the breakable tiles limit your opportunities to approach them as you like, but there’s still something peculiar about it. Because you can still jump when sliding on ice, and indeed sometimes have to in order to solve a level, ice tiles represent the only realtime element I’ve seen so far. Breakable tiles, meanwhile, really emphasize that this is at heart a turn-based game: you can sit on them for as long as you want, and during the entire time that they bear your weight, they play a wobbling, crumbling, just-about-to-collapse animation. But they don’t actually collapse until you move on.

The second cluster, “Jump in the Fire”, gives us springboard tiles, which catapult you forward three spaces (one space farther than you can jump), and then fire tiles, which start off dormant, but become deadly after you use them once. This is a similar pairing to the previous cluster: you get one thing that lessens your control over where you go and requires you to approach them from the right direction if you don’t want to go flying off the edge, and one thing that eliminates tiles from use. In fact, in practical terms, fire tiles and breakable tiles are usually equivalent. There are differences, but they’re subtle ones. Occasionally, you might want to drop through the space left by crumbled tile to a floor below. Also, remember that some levels loop around so that you can reach the flipside of your tiles. The reverse of a lit fire can be a normal tile; the reverse of a hole where a breakable tile used to be can’t.

Cluster 3, “Toggled Blocks”, is sort of an exception to the two-new-things-per-cluster pattern: the one new concept introduced here is switch tiles that turn things on and off. (Each togglable element can start off in either state, and if there are multiple switches, each switch toggles everything.) It’s still treated as introducing two elements, though, both of which are toggled by the switches: tiles that appear and disappear, and tiles with spikes that retract and extend. As with the breakable and fire tiles, these are mostly equivalent, just two different types of obstacle, except on levels where you need to pass through a disappearing tile space. But then, it seems like the levels here employ that trick a lot more. One notable thing about the switches: they’re the first element such that touching them can alter the board in a good way. Sometimes you roll onto a switch and immediately want to press it again to get things back into the state they were in before. It took me a while to realize that you didn’t need to roll off the switch and back on to accomplish this: you can do it by jumping in place.

After that, we get “Shifting Sands”: teleporters and sand tiles. Teleporters come in pairs, each sending you to the other — in fact, I’m not sure it’s possible for a level to have more than two. At any rate, they don’t seem like a very interesting trick to me. They’re not so much a thing that creates new puzzle opportunities as a convenience for the level designer, a way to avoid figuring out how to create a physical connection that doesn’t interfere with the puzzle. Sand tiles, now, that’s a thing to build puzzles from. The metaphor here seems to be drawn from sand traps in golf, which can only be got out of with great force. Likewise, you can’t roll out of a sand tile here: you can only jump out of them, leaping over the tile between. A grid composed entirely out of sand tiles would thus be broken into four mutually-unreachable sub-grids. Throw in a few ordinary tiles to permit crossing over and you have a very unintuitive sort of maze. Navigating sand feels a bit like a Knight’s Tour or something, forced by the rules to skip over the places you really want to go.

The fifth cluster, “Hidden Blocks”, I’ve only glanced at. It introduces tiles that are invisible until you get close to them, and then tiles that are visible from a distance but disappear close up (until you’re actually sitting on them). Both are rendered, when visible, in a way that suggests the reflections of light on glass. I can’t say I really like this addition to the game’s repertoire, adding hidden information to a puzzle type that was getting along without it before, and was otherwise quite good about letting me view the entire structure of each level freely. It may make for difficult puzzles, but it’s a cheap difficulty, and doesn’t make for better or more interesting puzzles.

That covers the first half of the game. After that, the introduction of new elements seems to stop, and the remaining clusters focus on different ways of applying what we’ve already seen. Based on what I’ve said above, I think I’m coming to the conclusion that the elements aren’t really all that varied. Not that this necessarily matters — sometimes a designer can do a lot with combinations of a minimal set of stuff. But it kind of seems like the designers here want to make it seem more varied than it is, which suggests a lack of confidence in their game elements.

0 Comments

0 Comments