World of Goo

And while we’re on well-regarded indie puzzle games, I might as well pull this one out. 2D Boy’s World of Goo has gotten enough good press that I didn’t hesitate to purchase it off Steam a few weeks ago when it was on sale, but didn’t have the time to start it. That’s happening a lot lately. Every weekend, Steam puts a large and temporary discount on one or more games, and it’s going to be the ruin of my attempts to reduce the Stack.

My first impression of the game is that it’s Bridge Builder crossed with Gish. Which is unfortunate, because those are both obscure enough titles that I’m going to have to explain them now. Bridge Builder (and its sequel Pontifex) is exactly what it sounds like: a heavily physics-based game in which you have to design river-spanning bridges that don’t collapse under their own weight under various physical and budgetary constraints. Gish, which is on the Stack still, is a gothy 2D platformer about a sentient blob of tar. Coincidentally (and somewhat oddly), these two games were made by the same team. Or perhaps it’s not coincidence: I’ve detected what may be shout-outs to Bridge Builder in WoG‘s first world, suggesting that 2D Boy is a fan of theirs, or at least aware of them.

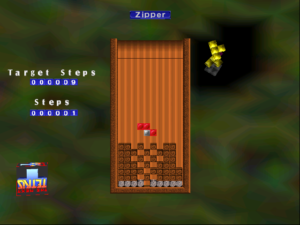

But to this a third influence must be added: Lemmings, with its chirruping doomed wee creatures that need your help to escape. The goal in each level of WoG is to help the roaming goo balls to reach an outflow pipe, usually by building a bridge to it out of their living bodies, which are most easily connected in triangular grids. Some species of goo can be detached and reused, others are effectively killed the moment you join them to your expanding structure. All survivors are sent to a special area with a competitive metagoal: build as tall a tower as you can, while clouds representing the tower-heights of other players on the net loom tauntingly overhead.

Even though I’m still in the lower ranks hieght-wise, I’m finding it gratifying to look at the details on those clouds and snicker at how much less efficient they are than mine — “He has twice as many pieces as me, and he’s only just a little way above me!” I only wish I could see their structures, rather than just their stats, because I’m curious about how other people are building their structures. (I suppose I should try Google. People must be posting screenshots.) My own best efforts are Eiffel-Tower-like: I start by making as large and as regular a triangle as I can, then when it’s thick enough, I start mining out the middle bits that aren’t needed for support any more, and put them up top. The broadness of the base, even when it’s reduced to a pair of legs, tends to minimize the structure’s wobble.

And yet it still wobbles. Wobbling is pretty much the point of goo; the whole game is built around what’s been called “jell-o physics”. For this reason, screenshots really don’t communicate the gameplay very well. You can look a picture of a nice slim tower and not realize that it’s swaying back and forth with an arc larger than the screen.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)