The Dark Crystal: Final Thoughts

Has it really been more than a week since my last post? Believe it or not, I haven’t abandoned the Oath. I just haven’t played any Stack games in the last week, owing to a confluence of (a) tax preparation, (b) nice weather, (c) the release of the new DROD demo (about which more soon), and (d) a certain amount of dread about continuing The Dark Crystal from where I left off, stuck near the end on one of those one-turn guess-right-or-die puzzles that plagued Time Zone. A nudge from a list of recognized verbs got me through that one, and the rest of the game was smooth sailing, aside from some more difficulties guessing the right commands to do things that I knew I needed to do. This game seemed to have that problem more than the other two games, perhaps because of the way that the necessary actions were chosen to fit a pre-existing story rather than designed to fit the game engine.

Has it really been more than a week since my last post? Believe it or not, I haven’t abandoned the Oath. I just haven’t played any Stack games in the last week, owing to a confluence of (a) tax preparation, (b) nice weather, (c) the release of the new DROD demo (about which more soon), and (d) a certain amount of dread about continuing The Dark Crystal from where I left off, stuck near the end on one of those one-turn guess-right-or-die puzzles that plagued Time Zone. A nudge from a list of recognized verbs got me through that one, and the rest of the game was smooth sailing, aside from some more difficulties guessing the right commands to do things that I knew I needed to do. This game seemed to have that problem more than the other two games, perhaps because of the way that the necessary actions were chosen to fit a pre-existing story rather than designed to fit the game engine.

The guess-the-verb problem is basically how most people remember text adventures. This may seem like an ignorant prejudice to a fan of modern IF, but it has its foundation in these older games. Especially the early illustrated games, where, as I’ve said, the emphasis in development was on the pictures rather than the gameplay, the story, or the prose. I keep being reminded of the ad campaign that Infocom ran in 1983, extolling the ability of prose to create more vivid images than graphics. Sierra’s games were a large part of the reason this was so convincing at the time.

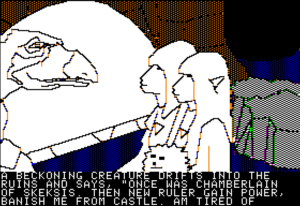

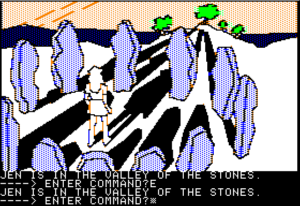

And yet, I think that if you wanted to make a better adaptation of the movie, the graphics, not the prose, is the main thing you’d have to improve here. The Dark Crystal is a more visual movie than many, and the Apple II is stretched to its limits just making a skeksis recognizable as a skeksis and a landstrider as a landstrider. It must have taken a great deal of work to get it even this far — creating graphics was a laborious process in the days before the mouse, and it looks to me like this game contains far more vectors per illustration than its predecessors. But even if you filled the game with still frames from the actual film at full cinema resolution, it would be less than satisfying: the puppeteer’s art is about movement. To really do this movie justice, you need animation.

I understand that there’s a sequel to The Dark Crystal in the works. I’m not sure how I feel about that, especially with the original creators uninvolved, but I definitely look forward to the inevitable game based on it. May it be a better representation of Froud and Henson’s world than this one.

Comments(1)

Comments(1)