Psychonauts: Missing Things

I think I’ve been missing things that the designers of Psychonauts wanted me to see.

I think I’ve been missing things that the designers of Psychonauts wanted me to see.

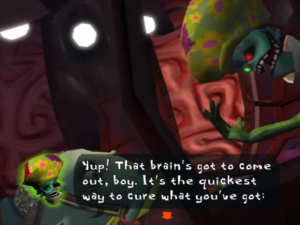

Early on in the game, Raz is given access to his own mental landscape, his dreamworld. There, he sees a mad doctor in a tower menacing Dogen, one of the other kids at the camp, and threatening to extract his brain. Raz is convinced that this is more than just a dream, that he’s witnessing something real. His default dialogue with other characters changes: he asks them if they know anything about people’s brains being stolen and things like that.

But after a while, Raz started saying things that suggested that he had observed changes in Dogen’s behavior that the stolen-brain hypothesis would explain. Thing is, I hadn’t observed these changes. I hadn’t seen Dogen in some time and had no idea where he was. I think I know where he was now: when I finally reached the brain-removal room in Raz’s dreamworld, the one thing that brainless Dogen said was “TV”. There’s a TV room in the main cabin, but I hadn’t visited it lately because there wasn’t much to do there. When I finally got back there (after a long diversion involving a monster lungfish), it was empty, and Raz said something along the lines of “Finally, no one is here! I can watch whatever I want!” Now, I had never seen anyone else in the TV room, and no one had ever objected to my changing the channel. So it really seems like I was supposed to have gone back there and seen Dogen, and possibly other debrained children, watching TV and drooling or something.

If I’m right about all this, and I’ve been breaking the sense of the story by not doing things in the right order, it’s kind of surprising: Tim Schafer comes from adventure games, and keeping the plot sensible regardless of player choices is a big part of adventure game design. But here I am, circumventing important plot points without trying. In fact, I’ve been at some pains to cooperate with the designers and do what they want me to do.

That may in fact be my problem, because the game sends mixed messages. On the one hand, Raz seems to regard the rescue of Dogen in the dream tower to be his top priority, and urgent to boot. It’s a false urgency, because the the game has no real time limits, but it seemed like a sign that this was what I was supposed to focus on next in order to keep the game going the way the designers intended. On the other hand, each step in the plot also changes all the incedental stuff: the kids are all in new places doing new things and have new dialogue, the bulletin boards have new notices, etc. (I didn’t even notice that the boards were readable at first, so I missed a couple of chapters worth of notices.) Most of this is just humor not related to the main story — there’s a fairly complicated pre-teen soap opera going on if you feel like paying attention to it — but some of it’s important to Raz’s investigations, and you’ll miss most of it if you actually go directly where Raz tells you to go instead of wandering around and visiting every location again every time you exit a dreamworld. I suppose I thought I’d always have the opportunity to stumble across relevant scenes involving the other kids on the campground, but at the point I’ve reached in the game, all the other kids are gone.

I may replay from the start at some point just to get a more thorough look at everything, maybe after I’ve finished the game and can understand all the foreshadowing. It’s an enjoyable game to play, and this would also allow me to see the earlier scenes at their intended framerate.

Comments(2)

Comments(2)