Bioshock: Hacking

Hacking is a big enough part of Bioshock that it has an entire suite of genetic modifications dedicated to reducing its difficulty in various ways. You hack safes and combination locks on doors to open them. You hack security apparatus such as cameras and automated gun turrets to make them switch sides, attacking your enemies and leaving you alone. You hack vending machines to lower their prices (no, you can’t get them to just dump their entire inventory for free), or even to make them offer additional items, which doesn’t make a lot of in-world sense, but I’ll accept the benefits anyway. Hacking a health dispenser not only reduces its cost for you to use, it turns it into an anti-health dispenser for enemies, killing them when they attempt to use it, and for this reason alone is well worth doing even if you don’t need the discount. In short, hacking has mostly the same uses as it did in System Shock 2, where the whole idea fit in a lot better. (I mean, even the word “hack” is anachronistic for a game set in 1960.)

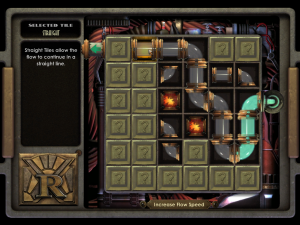

Hacking is done through a special minigame that takes over the screen. It’s basically a variant of Pipe Dream/Pipe Mania. You have a grid of tiles depicting tubing. You have to assemble them so that the fluid will flow from an inlet to an outlet, and you have to do fast enough to keep ahead of the fluid. Fail, and you either take damage or trigger an alarm. The genetic upgrades I mentioned mainly affect the play of the minigame in various ways: slowing the flow, reducing the number of unmovable blocker tiles.

Hacking is done through a special minigame that takes over the screen. It’s basically a variant of Pipe Dream/Pipe Mania. You have a grid of tiles depicting tubing. You have to assemble them so that the fluid will flow from an inlet to an outlet, and you have to do fast enough to keep ahead of the fluid. Fail, and you either take damage or trigger an alarm. The genetic upgrades I mentioned mainly affect the play of the minigame in various ways: slowing the flow, reducing the number of unmovable blocker tiles.

Before you go into the minigame, there’s a screen that shows you the estimated difficulty of the hack. If it looks too hard, or if you simply don’t like the minigame, you have other options, including backing out, using an automatic hacking tool, or even just bribing the machine. I guess this really is the consequences of Andrew Ryan’s philosophy taken to its extreme: even the security systems are free to take a better offer. Not that I’ve ever taken that option. Hacking tools are generally cheaper.

Before you go into the minigame, there’s a screen that shows you the estimated difficulty of the hack. If it looks too hard, or if you simply don’t like the minigame, you have other options, including backing out, using an automatic hacking tool, or even just bribing the machine. I guess this really is the consequences of Andrew Ryan’s philosophy taken to its extreme: even the security systems are free to take a better offer. Not that I’ve ever taken that option. Hacking tools are generally cheaper.

It’s by far the most involved, and to my mind the most engaging, of the hacking minigames in the Shock games. System Shock 2‘s hacking was basically a matter of clicking on dots in a grid that might or might not turn the right color to give you the three-in-a-row you needed. Your hacking skill affected the probability. System Shock 1 didn’t have as many uses for minigame hackery — mainly you hacked by swimming around in cyberspace — but it did have some control panels for security doors that you needed to rewire through a special rewiring interface, another guessing-game where you just tried permutations until you increased a meter to the right level. Neither of these is the sort of game you’d play by itself. They’re more WarioWare-like, little unit operations whose purpose is to make you briefly pay attention to something other than FPS action.

They did have a couple of things over the Bioshock hacking, though. For one thing, they were more believable in context, as user interfaces to whatever was really going on in the machine. Bioshock‘s pipes are I suppose thematic for a game set underwater, but they make you wonder just how these combination locks are constructed. More importantly, the System Shock 1/2 hacking minigames were integrated into the rest of the game a lot more smoothly. Hacking happened in your HUD. The rest of the world still went on around you. You could suddenly come under attack while hacking, and you’d have to stop hacking to respond. Bioshock’s hacking minigame makes a show of being delicate and time-sensitive, which it is, but only in its own time. You can hack a turret while someone’s shooting at you, and you won’t suffer any damage until you’re done. As one of the very first Zero Punctuation reviews pointed out, you hack ceiling-mounted security cameras that are just out of reach by jumping. You do the entire hack while airborne and don’t fall until you come out of the interface.

And, weird as each of those things is, they’re even weirder in combination. Given that hacking is completely separate from the rest of the world, the designers really could have put in any kind of minigame. They could have done something akin to Exploit. They chose pipes. Not that I’m really complaining. It’s still a pretty enjoyable minigame, and works well with the genetic upgrade system.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)