NightSky

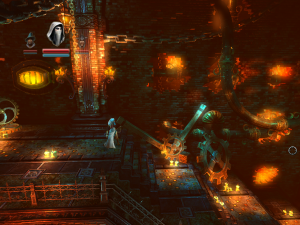

NightSky is the latest from Nicklas “Nifflas” Nygren, author of Knytt, and as with Knytt, most of the point of playing is to observe the stylish, elaborate-yet-minimalist visuals. This is a quiet game made out of silhouettes in various themes, levels with silhouettes of gears and levels with silhouettes of distant trees and so forth. A glowing glass orb navigates this environment under the player’s control.

NightSky is the latest from Nicklas “Nifflas” Nygren, author of Knytt, and as with Knytt, most of the point of playing is to observe the stylish, elaborate-yet-minimalist visuals. This is a quiet game made out of silhouettes in various themes, levels with silhouettes of gears and levels with silhouettes of distant trees and so forth. A glowing glass orb navigates this environment under the player’s control.

I suppose the spherical avatar begs comparison to Within a Deep Forest, Nifflas’ previous game with a ball for a protagonist, but the gameplay reminded me a lot more of Gumboy: it’s a heavily physics-oriented game where your main activity consists of just rolling left and right and trying to get enough speed to go flying off ramps to where you want to go. It doesn’t push this as hard as Gumboy did, though. NightSky is more about variations on the theme. The default controls include a button to speed up and a button to stay put (the latter being useful for clinging to moving objects), but some levels don’t allow them, or replace them with other things: the stay-put button activates a machine, or the go-faster button reverses gravity. Some levels even disable the move-left/move-right buttons and make you navigate entirely by manipulating the environment — say, releasing a hammer to smack a sled with the orb in it, or using a pair of pinball flippers. There are orb-driven vehicles, including ornithopters. It’s just one shadow of a thing after another.

The irrelevant frame tale involves dreams, and that’s a good way to think of this game: as in a dream, you just find yourself in situations without preamble or explanation. These situations last three screens, no more and no less. If there’s a navigation puzzle that only uses two screens, you get a third one that’s pure scenery. I rather like this pointless symmetry, although I’m not sure I can explain why.

The game offers both an easy and a hard mode, the difference affecting the content of the levels but keeping them roughly the same, like the light-world/dark-world thing in Super Meat Boy. It suggests reserving hard mode for your second play-through, and I agree that this is the correct approach for this game, as the hard versions of the levels are sometimes quite frustrating, and there’s a good deal of satisfaction in just breezing through the easy versions. After the epilogue, you can unlock a final set of “slightly nonsense” levels that break the game’s carefully-crafted ambiance entirely, with brightly-colored checkerboard levels and levels made of ASCII art and suchlike. It’s a good way to end it. I can’t really say that the game takes itself seriously, considering the orb-driven ornithopters, but it’s arty enough that the silly bonus content helps to strike a kind of balance. Braid could have used an ending like this one.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)