Unreal II: Summing Up

Playing all the way through Unreal II: The Awakening has done nothing to change my first impression: that it’s a pretty decent FPS in a military sci-fi setting that has very little to do with Unreal as I know it.

It’s got Skaarj, but despite a dramatic introduction, they turn out to not factor big in the missions or story; when you suddenly have to deal with a Skaarj invasion force occupying your home base in the penultimate mission, it comes as a surprise, in a “Huh? Those guys are still around?” way.  The main enemies in most missions are just human mercenaries, and the alien menace that comes to overshadow any mere human opposition towards the end is the Drakk, a race of hovering non-humanoid robots that live in a Gigeresque Borg palace, all black and ribbed and imposing. For my money, the Drakk world is the most satisfying alien environment in the game, more so even than the skin world.

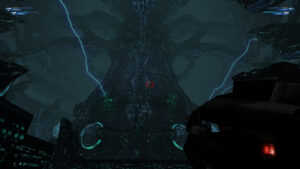

The main enemies in most missions are just human mercenaries, and the alien menace that comes to overshadow any mere human opposition towards the end is the Drakk, a race of hovering non-humanoid robots that live in a Gigeresque Borg palace, all black and ribbed and imposing. For my money, the Drakk world is the most satisfying alien environment in the game, more so even than the skin world.

But freed from expectations, it is, as I say, a pretty good single-player shooter, at least as I judge things. It’s got a good variety of weapons optimized for specific situations — albeit mostly it’s the standard assortment; the Shock Rifle, which I described as Unreal‘s signature weapon, never shows up, but we do at least get a chaotic-ricochets weapon and some other novel stuff. And the tactics, while pretty basic, are just complicated enough to be satisfying. Cover is a big factor — not in a Gears of War “press this button to take cover” way, but in that battlefields tend to be littered with rocks and pillars and things, and most weapons need to be reloaded periodically to render you temporarily helpless so you’ll need to take advantage of them. Temporarily incapacitating foes and taking advantage of the fact that they’re not shooting you is a big factor — usually this means knocking them down with a weapon that exerts strong force, such as a shotgun or rocket launcher, but the game’s quirkiest weapon, the spider gun, does it by covering them with spiders, making them run around screaming “Aaah! Get it off!”

The final mission, on a spaceship that’s plunging into a sun, does one of my favorite FPS tricks: playing with gravity. And not just the amount of gravity, letting you make huge slow leaps, but the direction, slowly rotating a hallway as you walk down it, leaving you walking on the wall and struggling to reach the handle of the door out. Now, according on a couple of web searches I just did, the unmodified Unreal Engine does not in fact have the ability to change the direction of the gravity vector. So the game is most likely just rotating the level geometry in that bit. But in the moment, when done in combination with the the floaty sensation that comes from weakening gravity’s strength, it really feels like it’s gravity that’s rotating, not the hallway.

I’m left not quite sure what the Awakening in the title refers to. The story concerns a macguffin that’s been split into seven pieces hidden on different planets, with various armed forces vying to reunite them and control their power. That power turns out to be the power to unlock the genetic potential in a particular alien race, turning them into huge nigh-unstoppable monsters that make you instantly regret your actions. So, that could be the Awakening: the awakening of the dormant monster genes. But that whole deal takes up a very small portion of the game, at the very end, and before that point, I really thought the “Awakening” referred to the Drakk, who also came out of a millennia-long hibernation to suddenly become the game’s major threat.

Finally, let’s talk about Dalton’s confrontation with the treacherous commander who sent him after the artifact pieces in the first place, pretending the orders came from Colonial Authority top brass but really intending to use the artifact for his own rise to power. Now, the obvious way to end his narrative arc, and the most poetically just, would be to see him meet his end at the hands of the monsters he created. Instead, Dalton shoots him dead in a cutscene after a bit of noninteractive dialogue. I assume that the writer felt it important that Dalton is involved in every major story beat, or at least the climactic ones. Just Dalton, though — not the player. That’s strange. It smacks of Hollywood thinking, really: we’re expected to experience agency over the player character’s actions because we identify with the player character, not because we’re performing those actions. The other peculiar thing about it is that, unlike all the other big confrontations in the game, it isn’t a fight: the guy isn’t even armed, and Dalton just murders him. And yet, judging by the camera work and the music, we’re clearly supposed to regard it as a big glory moment, where the audience throws up their hands and cheers for frontier justice. Maybe this is why it’s noninteractive. Maybe players were hesitating to shoot anyone who wasn’t shooting back. Maybe they wouldn’t hesitate in another game, one based on the just-shoot-everything principle, but this game trains you not to kill peaceful NPCs through its numerous defense missions and interstitial dialogue sequences.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)