Games Interactive: War of the Words

I’m well on my way to clearing out the Special Crosswords. All I’ve got left is one that’s ornery and one that’s clueless. But to my surprise, there was one, which I solved last night, which was neither. Listed by an individual name, “War of the Words”, rather than by a type, it didn’t have a one-star difficulty rating like the Cluelesses or a three-star difficulty rating like the Orneries. It had two stars. What could it mean?

I’m well on my way to clearing out the Special Crosswords. All I’ve got left is one that’s ornery and one that’s clueless. But to my surprise, there was one, which I solved last night, which was neither. Listed by an individual name, “War of the Words”, rather than by a type, it didn’t have a one-star difficulty rating like the Cluelesses or a three-star difficulty rating like the Orneries. It had two stars. What could it mean?

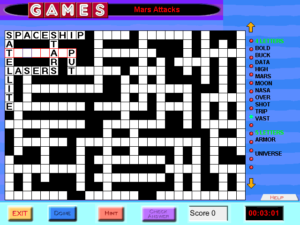

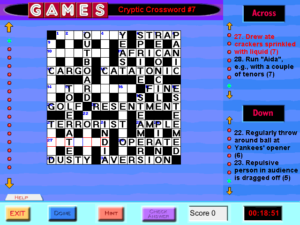

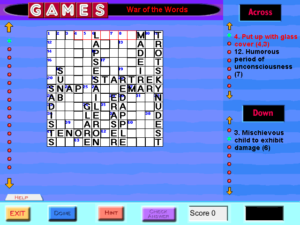

As you’ve probably already seen from the screenshot, it’s a crossword in the “barred” grid format, its words separated by heavier border lines instead of black squares. I remember seeing this format in the magazine. It’s basically a signal. It says “This one’s serious. It may even be British.”

Unlike everything else under Special Crosswords, it comes with no special instructions — just the normal explanation of how to scroll the clues and use the Hint button. This doesn’t mean there’s nothing special about it, it just means that you’re expected to figure out its special features without instruction. It doesn’t take long to discern that it’s a cryptic, just because the clues have that peculiar two-part cadence to them. But the designated cryptics have instructions about how to solve cryptics, and this doesn’t. I don’t think this is a mistake on the part of the game. I think it’s how it was originally published. And the thing is, a lot of the cryptic clues don’t quite work. Take 23-Across: “Sleep break”. The answer is “snap”. “Snap” is a synonym for “break”, and “sleep” clearly clues the “nap” part, but where does the inital S come from? Not from the clue. It goes against what I was saying about cryptics before, that the clues are self-contained and self-confirming. But in a puzzle like this, where you haven’t been promised anything about the rules, it just means that there’s a rule you haven’t discerned. Spot enough anomalies of this sort and you start to notice a pattern. And that’s a sort of puzzle I adore.

In this collection, there’s a bug that seems to be unique to this one puzzle, possibly because it’s in a different format than the rest of the crosswords: it tries not to select Down words. If you have a Down word selected, and you press enter to advance to the next clue, it will instead select an Across clue that crosses it. If you try to switch from Across to Down by clicking on the current square, it just doesn’t work. In most cases, I was able to find an uncrossed letter I could click on to force it into a Down, and once it was there, it obediently let me move the cursor around within that word. But there are some Down words that are crossed at every letter, and that makes them simply unselectable. Fortunately, the very conditions that make this happen mean that you can fill in every letter anyway.

Comments(2)

Comments(2)