Bloodnet: People and Humans

The interaction in Bloodnet is unintuitive. Even the mere acts of walking around, picking up objects, and talking to people don’t conform to the usual expectations of point-and-click adventures. To move, you press the left mouse button and hold it. Stark will move towards the cursor as long as the left mouse button is held down. Because of this, doing anything else, such as picking up objects or talking to people, uses the right mouse button. And anything more complicated, such as modifying your hardware or venturing into cyberspace, has a system of rules and meanings to learn on top of its own unintuitive UI.

So I think I’ll be learning the systems here one at a time. In the starting phases, I can get away with just wandering Manhattan and talking to people. Recruiting a posse. Unwelcome combat encounters, it turns out, can largely be avoided just by not wandering around completely at random. Sticking to the places mentioned in Stark’s uncomfortably verbose contacts list, and places that people you meet in those places tell you about.

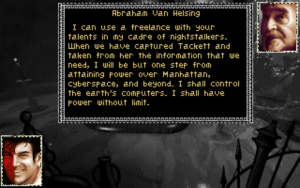

Most dialogue is lengthy and noninteractive. You right-click on someone and you get several paragraphs of text, laden with made-up hacker jargon, maybe punctuated by a yes-no question, usually about whether you accept the person’s asking price to join your party. One peculiar thing: The game will give you either printed text or voice acting, but not both. And it’s governed by whether or not you have sound enabled. “Sound”, mind you, is separate from music. Heck, it’s willing to use two different devices for them, so you can play sound through your Soundblaster Pro and music through your Roland LAPC-1. That’s this game’s vintage. And, as such, unwritten standards about how to present dialogue in an adventure game were not completely settled yet. Voice acting seems to be something of an afterthought here; if you use it, it goes into the same dialogue UI presentation, desaturating the scene and placing character portraits at opposite corners, but the bulk of the screen, where it would otherwise be putting the text, simply goes unused. It feels a bit like listening to a radio drama. One with hammy acting.

I’ll say this for it: at least the character dialogue is more true to cyberpunk literature than in most so-called cyberpunk games. The minor NPCs are ethnically and racially diverse, and largely downtrodden and traumatized. Some rely on cybernetics because they’re disabled. They form street gangs with names like “Flux Riders” and “Electric Anarchy”, living in squats where they can tap into cyberspace illegally, fighting the Man, or rather, the TransTechnicals megacorp, which basically rules Manhattan and is secretly run by vampires.

Stark himself fits into the category of “relies on cybernetics because of disability”. Even before he got vampirized, he was a victim of “Hopkins-Brie Ontology Syndrome”, a neurological condition that sometimes strikes deckers, making their perceptions of cyberspace and meatspace blur together. The implant helps with that, stabilizing his mind. It’s just a lucky coincidence that the stabilization helps him resist vampiric mind control. There may be a Christian allegory in there. His strength results from his imperfections.

But regardless of the religious implications, I think this aspect is worth paying attention to in light of more recent cyberpunk discourse. There’s been some complaint lately about cyberpunk-themed games presenting Cybernetic Augmentation as reducing your Humanity, asking “Are you truly human when you’re part machine?” and so forth, a question that’s frankly insulting to anyone with a medical implant or prosthesis. Indeed, such devices can be powerful tools in restoring a person’s sense of their own humanity, by enabling them to participate in society in ways that might otherwise be lost to them. Bloodnet has a “Humanity” stat, but it’s not about Stark becoming less human as he becomes more cyborg. It’s about him becoming less human as he becomes more vampire. Cybernetics is how he resists that.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)