Syberia: From Komkolzgrad to Aralbad and Back and On

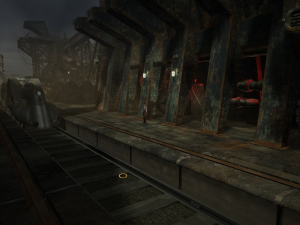

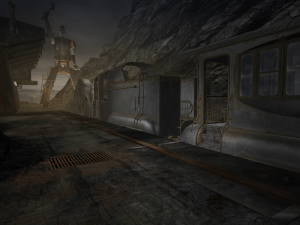

The remainder of Syberia went rather smoothly, despite a couple more missed hotspots. The final two stops are interlinked in a way that the first two were not, so I felt it made sense to take them both in a single sitting.

What happens is, Kate’s quest for Hans is temporarily replaced by a quest for hands. In the abandoned industrial town of Komkolzgrad lives a disfigured creep who, in the tradition of his kind, is obsessed with an opera singer named Helena Romanski. He steals the hands of the automaton driver of Kate’s train, and tells Kate he’ll give them back when she brings him Helena, to perform for him once more, like she did many years ago. This prompts a side-trip to the moribund resort of Aralbad, where she’s living out her twilight years. Since you can’t take the train, you instead go by suspiciously convenient dirigible. The combination of airship and opera put me in mind of Final Fantasy VI. I even briefly entertained the notion that instead of hunting the diva down, I could impersonate her like Celes impersonated Maria, but this story isn’t quite that silly.

The reason that the disfigured creep stole the hands in particular was to use them on an organist automaton of his own creation (after Hans Voralberg’s designs), specifically designed to accompany Helena. When he reneges on his bargain and tries to keep both Helena and the hands forever, Kate has to detach the hands from the organist with a screwdriver. When I reached this point, my reaction was “Why didn’t she do this before?” Kate had both the screwdriver and access to the organist back in her first visit. She could have skipped Aralbad altogether if the game had put a hotspot where there was one now. Thinking about it afterward, I think the intention was that the hands I first saw on the organist were not the stolen ones: they were cruder ones, without the dexterity to properly play an organ or drive a train. But this was not clear to me at the time. As with the mammoth drawing, it would have clarified matters enormously if I were allowed to try and fail: I could have detached the hands and brought them to the train, only to be told that they were the wrong ones.

Oddly enough, the train also goes through Aralbad, and it is on returning there that Kate quite unexpectedly finds Hans, a little old man with an unworldly manner. I didn’t expect to find him before reaching Syberia, but that doesn’t happen until the sequel, and I suppose Sokal wanted to end the first game in some kind of victory, even if the story is left unresolved.

Ah, but whose victory? Well, Kate does achieve her original goals. But Hans accepts the news of his sister’s death and signs away the factory with remarkable equanimity. His man-child incomprehension means the adult world cannot touch him, and that is his triumph. Kate can do nothing in the face of this but defect: throwing her career to the wind, she joins him on the train for further adventures. For my part, I think I’ll take a bit of a break before joining them.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)