So, I decided on a whim to leave Outland for a while and do some more questing back in Azeroth. I picked the desert province of Tanaris for no better reason than that I hadn’t been there yet and it was right next to Thousand Needles, the last zone I had completed. By pure coincidence, it turns out that Tanaris contains the entrance to a Burning Crusade dungeon that I was an appropriate level to attempt.

This is unusual. I don’t usually access dungeons through their entrances. The Dungeon Finder makes it unnecessary. I’ve been through all of the dungeons available without expansions, and for many of them, I still have no idea what zone they’re in or what the motivating context is supposed to be. For me, the motivation was usually that I was about to become too high-level to access that dungeon through the Dungeon Finder. Perhaps this is part of why I’ve always found it difficult to get up to speed about what I’m supposed to be doing in them (although mostly that’s just because most of the people in the average pick-up group have done the dungeons before and go running off without bothering to read the quest descriptions).

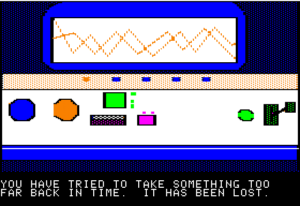

Here, though, not only did I actually get the context, but the context seemed important, because it was an unusual dungeon. For one thing, it was outdoors. That’s not unprecedented — heck, it’s not even the only open-air dungeon in Tanaris. More importantly, it’s set in the past. The whole thing is set in a modified copy of the Hillsbrad zone, accessible through a magical cave, a special place where stresses on history manifest. There’s a whole order of temporal guardians living down there, willing to give a tour to any adventurers who can help them iron out their enemies’ attempts at altering history. Old Hillsbrad isn’t the only time and place where this battle is being waged, but it’s the only one accessible to me at the moment.

The attempted revision involves an orcish slave named Thrall. At the time of The Burning Crusade, Thrall is leader of the Horde, and the path to that starts here, with his escape. This is therefore one of those moments when a great deal of history hinges on a single action, and is thus vulnerable to meddling.

Now, Thrall isn’t the leader of the Horde any more: as of Cataclysm, he’s been replaced with Garrosh Hellscream. But over in Outland, which hasn’t been revised, Thrall is still in charge. There’s a lot of that sort of thing going on, really. Different places, in a sense, occur at specific points in the ongoing storylines. It used to be that taking the expansions in order would give you events in order, but Cataclysm messed that up by changing the core zones back on the original continents, giving them a new plot set in the aftermath of Wrath of the Lich King. Even within a single zone, time can get messed up, as when you talk to an NPC before you’re instructed to, and then later when you approach him in-sequence he greets you as if for the first time. There’s a whole series of events back in Silverpine Forest involving an Undead NPC named Lord Godfrey: he gets raised as Undead, accompanies you on some quests, and ultimately turns traitor and flees to a dungeon called Shadowfang Keep, where he’s the end boss. I saw the last part of that first. Confusion ensued. What I’m getting at is that there are really time portals all over the place. The only thing unusual about the Cave is that they’re openly acknowledged by NPCs.

Playing as Horde makes helping Thrall a natural thing to do, but apparently the premise and quests are the same regardless of which team you’re on: keeping the timeline sound is an overriding concern for everyone except omnicidal madmen. This must be one of the few points in the game where Alliance players get to see things from the Horde point of view, see the future Horde leader as a proud and honorable ally suffering injustice at the hands of sneering, overbearing humans. Horde players get a taste of how the other half lives, too: they spend the entire mission shape-shifted into humans so they can infiltrate the place, and if you wander off-course enough, you can talk to peaceful human villagers, and listen in on their private conversations.

Come to think of it, this reversal of perspective works well into Burning Crusade‘s overall themes. As I mentioned before, the premise of the expansion involves Horde and Alliance putting aside their differences to deal with a demon invasion. Ironic, then, that I’ve been attacked by Alliance players more often in Outland than anywhere else.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)