Sam & Max: Musings on finishing Season One

Now that I’ve completed all six episodes of season one, I’m wondering if mine was the best approach. Is it better to actually play the episodes episodically? Playing them as they come out undoubtedly lets you participate more in the Sam and Max fan community, speculating about things to come, even influencing the later content (as Merus points out in comments to my last post). But playing through the season all at once probably makes for a meatier experience. At one point in episode 6 (the last of the season), Max plays a videogame within the game, and complains “It was too short and not hard enough. I want my money back!”, an obvious dig at complaints in the forums. I haven’t followed the forums, but it’s inevtiable that people would make this complaint, as each episode takes just a few hours to play.

But I suspect I wouldn’t share that complaint anyway. I’m accustomed to short adventure games, thanks to the Interactive Fiction community and the annual comp in particular, so these episodes struck me as about the right length. Or possessing about the right amount of content, anyway. The episodes actually take longer to play than a typical comp game, but only because of the time spent walking Sam around from place to place — something I grew impatient with at times, and wished for a faster way to travel. (There’s a “warp drive” checkbox in the options menu, but apparently that’s just Telltale’s version of silly clowns.) So I may be one of the few people who wanted the episodes to take less time.

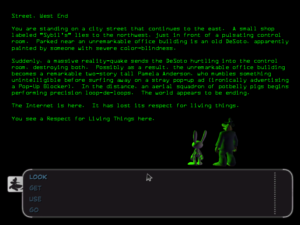

I wonder how much the folks at Telltale are aware of modern non-commercial IF? The Sam and Max games certainly show an awareness of their text-adventure heritage. Episode 5 features a whole scene set in a text-based environment, with Sam and Max themselves as the only graphical elements — a very stylish effect, I thought. It even uses that perennial only-possible-in-text gimmick, treating abstractions as tangible. Plus, there’s a sly shout-out to Zork in the beginning of Episode 4, subtle enough to pass unnoticed by the uninitiated. But the main influence on these games seems to be the classic Lucasarts games. Which may seem too obvious to point out — the first Sam and Max game was Lucasarts, after all, and Telltale seems to have quite a few Lucasarts refugees on staff. But what I mean here is the little touches, like the way responses to significant actions get shorter on repetition, and the way dialogue is used to provide hints disguised as jokes.

I wonder how much the folks at Telltale are aware of modern non-commercial IF? The Sam and Max games certainly show an awareness of their text-adventure heritage. Episode 5 features a whole scene set in a text-based environment, with Sam and Max themselves as the only graphical elements — a very stylish effect, I thought. It even uses that perennial only-possible-in-text gimmick, treating abstractions as tangible. Plus, there’s a sly shout-out to Zork in the beginning of Episode 4, subtle enough to pass unnoticed by the uninitiated. But the main influence on these games seems to be the classic Lucasarts games. Which may seem too obvious to point out — the first Sam and Max game was Lucasarts, after all, and Telltale seems to have quite a few Lucasarts refugees on staff. But what I mean here is the little touches, like the way responses to significant actions get shorter on repetition, and the way dialogue is used to provide hints disguised as jokes.

That last point reminds me a little of something John Cleese said about writing Fawlty Towers. The audience of a comedy show, according to Cleese, knows that anything that doesn’t lead into a joke immediately is a setup for a joke later on, and this robs the later joke of some of its impact. So he tried to make sure that all his setup material also yielded immediate humor, so that the viewer would be surprised at what was referenced again later. The principle is similar here, except that the goal isn’t (solely) an unexpected joke, but a moment of realization, when the player suddenly understands something’s significance without it having been shoved in their face.

Speaking of disguising your material, I notice that episode 5 keeps the whole business of doing things in threes (despite what I said before about episode 4 breaking the patterns), but tries to hide it by inflating numbers: there’s a group of four machines, of which one is useless, and a quest to obtain five gold coins, of which three are found together.

The threes come back with a vengeance in episode 6, though, with a very satisfying pre-endgame that puts Max in the center of a story. It seems pretty important to me that this happens. Of the two main characters, Max is the more emblematic of what they are, more gleefully chaotic, more disarmingly cute. If you see one of the duo alone in any context, it’s pretty much always Max. But these qualities also make him a difficult player character, and so for most of the story told by these games, he plays the role of Sam’s wacky sidekick. Even after he becomes president of the United States in episode 4, he’s Sam’s wacky sidekick whose wacky features include the presidency. But in episode 6, he becomes for a while the focus of the player’s attention, the thing that the puzzles are about.

Comments(3)

Comments(3)