Blue Prince has a lot of repeated iconography. The holly leaf with three berries, the crescent moon with a circular hole in it. The shapes that are symbols of the various nations. But the most mysterious of its symbols is the spiral. There are four handwritten notes you can find (only three of which I’ve seen in-game) that all bear a picture that incorporates a spiral, together with a short phrase — “Denoted in verse”, “Investor needed”, “Does it never end?” — all of them anagrams of each other. No one knows why. It’s one of the game’s great unsolved mysteries.

The most concrete thing we know about it is that the “Does it ever end?” note depicts the “Spiral of Stars”, a large constellation visible from the house’s Observatory. On every day that you visit the Observatory, you can see a collection of constellations and click on them to trigger special effects for the day, like giving you an extra key or reducing the prices in shops or making dead ends come up more frequently, the effect being described in text next to the constellation when you select it. Uniquely, the Spiral of Stars has effects that evolve: every time you trigger it, another word is added to the text, and any completed phrases take effect immediately. It’s one of those incremental progress deals that I was describing, that give the player one more reason to keep coming back day after day, and it keeps adding to the text for far longer than you’d expect, making “Does it never end?” appropriate.

But of course it does end eventually, after adding 100 words, to match the 100 stars in the constellaiton. And at that point it’s basically used up. For most of its lifespan, the Spiral of Stars is the most beneficial constellations there is — the first several effects give you loads of resources that help you on your run. But the last several prevent you from obtaining more of those resources that day, making it only useful at the end of a run, and the very last effect to be added simply ends the run immediately, making the Spiral of Stars useless forevermore.

It could be warning to players about taking their obsessions too far. In fact, it almost certainly is. Let me tell you about the game’s second ending. This is going to get really spoilery.

So, one of the first things you learn about popular children’s author Marion Marigold, most likely before you learn that she’s your mother, is that she wrote a book called The Red Prince, about a prince who’s obsessed with the color red and won’t look at any other colors. She claimed in public that it was simply inspired by her son’s (that is, the player character’s) unreasonable fondness for the color red, but the authorities thought it was secretly subversive: every nation in this fictional world is associated with a color, and red is the color of Fenn Aries, the nation where the game takes place. And so she was forced to change the ending, in which the prince finally looks at the sky and decides he likes blue better, as it might be taken as a political statement. The published version instead goes meta, talking obliquely at first about the prince’s favorite book and concluding that the prince is the reader and the book is The Red Prince.

(Side note: This isn’t just a matter of fictional small nations ostensibly located in Europe, like Latveria or Freedonia. We can find maps and even globes in the house, and they show landmasses that are not those of our Earth. It’s quite strange to discover, when the game is fairly advanced, that it’s set on another planet, especially when you know that this alien world shares our calendar and even celebrates Christmas.)

Was The Red Prince actually meant as a political statement? Sort of. The ending cutscene, in which Mary reads the original text over a montage, suggests that she wrote it as a gentle warning to her son to not be seduced by Fenn Aries propaganda. She wanted him to be able to see past it, in part because she knew the family’s big secret: royal blood, from the kings that Fenn Aries deposed.

Much has been made of the “layers” of Animal Well, with each layer being associated with collecting all of a particular thing, and the first two layers triggering a credits sequence when they’re completed. Blue Prince doesn’t separate its layers quite so cleanly, but I think we can usefully describe layers in a way that isn’t greatly dependent on the details of the game. Layer 1 is simply completing the game’s initial goal, and in these games, is basically achievable by a reasonably on-the-ball player who’s enjoying the gameplay enough to keep at it long enough. Layer 2 has its own goals, and is where most players will need a few hints, but is still mostly approachable solo. Layer 3 is a community effort: people are expected to solve it by sharing information and theories, so the clues are allowed to be too obscure for most people. Layer 4 is where there’s no reasonable expectation that it will ever be solved.

The focus of Blue Prince‘s second layer is acquiring the components of a ritual. And not just any ritual: a coronation. Simon takes his place on the lost throne of Orindia Aries, and in doing so unlocks the way to the second ending. And there’s some pretty great fusion of puzzle with tile-plpacing game here, as you figure out how to get everything you need together in the house under some pretty severe constraints. (There are multiple viable approaches to this.) But it’s a little peculiar, because it’s not a real coronation. You can’t just declare yourself king all by yourself in an empty house without anyone knowing about it and expect anything to actually change in the world outside. And I feel like the second ending is basically an acknowledgement of this.

What it all leads to is this: In a small secret room under the house, you find three boxes in different colors, a familiar sight from a logic puzzle found in the Parlor, where you have to figure out which box contains a prize. This time, though, it’s not a logic puzzle. It’s a choice. The blue box — the color of your coronation — is labeled “This is the end of this journey.” The black box — the color of the old kings — says “There is no end to this journey.” And the white box says nothing about journeys and is irrelevant to this discussion.

And the boxes more or less give what they promise. If you open the blue box, you find a manuscript for a book called The Blue Prince, which is basically The Red Prince turned backward and made even more meta: where the published version of The Red Prince talks about “the red book we just read”, The Blue Prince talks about “the blue game we just played”. If The Red Prince was written to gently chide Simon for his Fenn Aries patriotic sentiments and warn him off of going too far down that path, The Blue Prince is there to similarly warn the player off of becoming too obsessed with the game.

The black box, now, the one that says “There is no end to this journey.” The black box is empty. But on the inside of the lid, the wood grain forms a spiral.

I think the message is pretty clear. When you find Room 46 and roll the credits, you have a clear opportunity to declare that you’re satisfied and stop playing, but the fact is, you’re probably not satisfied at that point. There’s way too many things you still want to investigate. But The Blue Prince basically says “No, really, you can stop now.” It doesn’t give you a video cutscene like the first ending did, but it does conspicuously give you the words “The End” on the last page. And if you don’t listen? You’re on the spiral.

And, as with the Spiral of Stars, the earlier parts of the spiral have good stuff on them! I’ve seen people say that Layer 3, the part with the Atelier, is the best part of the game. Alas, after deciding I was done, I spoiled myself about that part too much to get any big “Aha!” moments out of it. But I’ve also seen people on the game’s Discord who are deep into the end of the spiral, grasping at straws to read meaning into the tiniest of incidental details. And I’m sure that they’ll continue to occasionally find actual secrets for some time — there are still some conspicuous clues in the game that no one knows how to interpret. But they’re definitely falling prey to what Mary tried to warn them about. Part of the genius of Blue Prince is the way that it uses the tile-placing game to slow down the player, making discoveries partially reliant on chance, using partial reinforcement to make the game more compelling, even addictive. This is also what makes it dangerous.

Games that are trying to be edgy sometimes make the exasperating decision to clearly push the player into doing things and then scold them afterwards for doing what it seemed like it wanted. Blue Prince could be accused of treading into that territory here, but I think it’s skirting the edges of it. It helps a lot that it’s done in Mary’s voice.

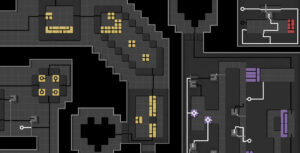

Here’s something new and really cool that became my obsession for a few days last week and which I’ve been mulling over ever since. At heart, 0PLAYER is a game about sliding tiles around on a grid to form connections between things, according to mechanics you discover over the course of the game, solving mini-puzzles that together form one large puzzle. Except it’s not interactive at all. The game is just a static image.

Here’s something new and really cool that became my obsession for a few days last week and which I’ve been mulling over ever since. At heart, 0PLAYER is a game about sliding tiles around on a grid to form connections between things, according to mechanics you discover over the course of the game, solving mini-puzzles that together form one large puzzle. Except it’s not interactive at all. The game is just a static image. Comments(3)

Comments(3)