So, I’ve finished all five cases in CSI: Hard Evidence. All in all, I enjoyed this game more than I expected to. The chief thing to recognize is that it’s not at heart a mystery game, but a treasure hunt. This was clearest to me at the beginning of the fifth case, where you have to spot a number of bullets lodged in walls. I wish more of the scenes were as clue-rich as that, because it was one of the high points of the game.

I mentioned before that the game automatically tags with a green checkmark those scenes and clues that have been exhausted as information sources. This is just one of several “assists” that can be disabled from the options menu. Personally, I kept them all on, despite my complaints about the game being too easy: it seemed like disabling them would make the game harder in the wrong ways, extending the time spend searching fruitlessly in the wrong places and so forth. There was a point where keeping them on actually got me stuck for a while, though, when I didn’t yet understand that a DNA sample got its checkmark simply by being identified, and that this didn’t mean it was no longer of use in comparison to other samples.

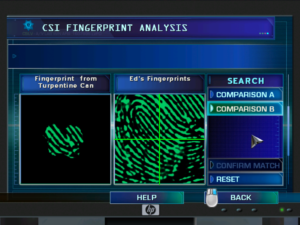

So, yeah, it turns out that it is possible to get stuck after all, at least temporarily. Several forms of evidence processing involve comparing two pieces of evidence, and once you have many individual pieces of evidence, the combinatorial explosion makes it inconvenient to just cycle through all the pairs. So you do have to have some idea of what you’re looking for, some of the time.

There are some good things going on in the game’s UI. Like the navigation: I mentioned before that it’s based on clicking between nodes in a continuous 3D environment, but even more than that, the graph of these nodes is a tree, and clicking the right mouse button moves back up the tree towards your point of entry. The nice thing about this is that exactly the same interface is used for other tree-like UI elements, such as cancelling out of a menu. While I wouldn’t suggest that every game adopt an interface like this, it does seem like a good choice for games in settings where the player shouldn’t be able to get lost.

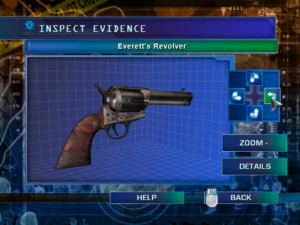

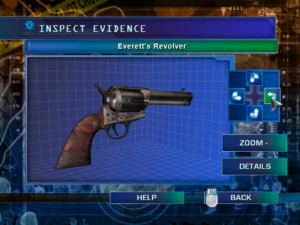

There are points that I definitely think could be improved, though. Nonstandard scrollbar behavior is my perennial gripe about homebrew GUIs, and while this game doesn’t have scrollbars per se, it does have button-based scrolling interfaces which don’t respond to the scrollwheel. It’s not even as if the game engine doesn’t have scrollwheel support: when viewing evidence, you can use the scrollwheel to zoom in and out. And speaking of viewing evidence, the controls for rotating items while inspecting them seem less than ideal. There are four buttons to the right of the view that can be clicked or held to rotate in two directions about two axes. But the axes are relative to the object, rather than the view, with sometimes unintuitive results. Plus, using buttons at all seems a little strained in a game that, in the scene views, normally handles rotation by moving the mouse to the edges of the screen. (Sometimes this even results in keeping an object at the center of your view and circling it, an effect similar to rotating an object in the evidence view.)

There are points that I definitely think could be improved, though. Nonstandard scrollbar behavior is my perennial gripe about homebrew GUIs, and while this game doesn’t have scrollbars per se, it does have button-based scrolling interfaces which don’t respond to the scrollwheel. It’s not even as if the game engine doesn’t have scrollwheel support: when viewing evidence, you can use the scrollwheel to zoom in and out. And speaking of viewing evidence, the controls for rotating items while inspecting them seem less than ideal. There are four buttons to the right of the view that can be clicked or held to rotate in two directions about two axes. But the axes are relative to the object, rather than the view, with sometimes unintuitive results. Plus, using buttons at all seems a little strained in a game that, in the scene views, normally handles rotation by moving the mouse to the edges of the screen. (Sometimes this even results in keeping an object at the center of your view and circling it, an effect similar to rotating an object in the evidence view.)

There’s also some stupidity in the way the game handles computers: your CSI toolkit contains a “USB data drive” that “detects encrypted data”, which is trivially decryptable by your lab equipment. Furthermore, people in this gameworld seem to be in the habit of encrypting their incriminating emails rather than deleting them. (Heck, just not encrypting them would be enough to escape detection here. It’s not like the game ever gives you the opportunity to read data that isn’t encrypted.) But I’m assuming that this is all inherited from the TV show. Plus, I may just be more sensitive to this than other simplifications made for the sake of gameplay. Goodness knows the fingerprint matching is greatly reduced from how it would work in real life, and the idea of getting a chemical analysis of a substance by sticking it in a chemical analysis machine is probably even more galling to chemists than anything done with computers here.

A certain amount of stupidity of content isn’t the only thing it inherits from the show. There’s the “bumpers”: when you go from scene to scene, you often get a brief montage of aerial views of Las Vegas, signifying “new scene” to the viewer. This is invariably followed by a “Loading” screen, which seems a little redundant, because it signifies the same thing. I suppose the limitations of the technology prevent it from displaying the bumper while loading the new data.

Another thing inherited: product placement. It’s not as blatant as in Lemmings 3D or Getting Up: Contents Under Pressure, but one of the cases has a subplot involving possible credit card fraud, and goes out of its way to mention how professionally those folks at Visa dealt with it, as well as just use the word “Visa” in preference to “credit card” wherever possible. (A print ad in the game’s documentation makes it clear that Visa is in fact sponsoring the game, or at least its documentation.)

So, would I recommend this game to people who aren’t fans of the show? No, not really. But perhaps I would as a study of graphic adventure techniques. It’s working with a limited palette, but it does a few interesting things I hadn’t seen before.

Disclosure: I received this game for free from Telltale Games.

Comments(0)

Comments(0)