TCoR:EfBB: Through Riddick’s Eyes

The Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay was released in 2004, which seems to be something of a turning-point year for graphics in games: this is the first game I’ve played in my chronological run-down that doesn’t look old-fashioned. At least, not to my eyes, which are probably kind of old-fashioned themselves. We’re almost up to the point in time where I more or less lost track of what was happening in “core” gaming, due to the release of new gaming consoles that I wasn’t about to buy immediately, not when there were so many brilliant indie PC and Flash games to download. In comparison to those, at least, Riddick looks positively futuristic, all highly-detailed textures with differing sheens and convincing dirt and bloodstains. There’s something about the surfaces that really reminds me of technology demos for graphics cards — probably the conspicuous bump-mapping. I guess it’s a good thing that nearly all the characters are either shaven-headed prisoners or helmeted guards, because it really minimizes the number of plastic-looking bump-mapped hairdos you see.

The Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay was released in 2004, which seems to be something of a turning-point year for graphics in games: this is the first game I’ve played in my chronological run-down that doesn’t look old-fashioned. At least, not to my eyes, which are probably kind of old-fashioned themselves. We’re almost up to the point in time where I more or less lost track of what was happening in “core” gaming, due to the release of new gaming consoles that I wasn’t about to buy immediately, not when there were so many brilliant indie PC and Flash games to download. In comparison to those, at least, Riddick looks positively futuristic, all highly-detailed textures with differing sheens and convincing dirt and bloodstains. There’s something about the surfaces that really reminds me of technology demos for graphics cards — probably the conspicuous bump-mapping. I guess it’s a good thing that nearly all the characters are either shaven-headed prisoners or helmeted guards, because it really minimizes the number of plastic-looking bump-mapped hairdos you see.

The game is basically a first-person shooter with stealth elements. Or at least, the opportunity for stealth. My own experience is that stealth generally works here like it does in Dungeons & Dragons: it usually ends in a big fight with all the guards, because that’s so much easier to pull off successfully. There’s an explicit “stealth mode”, which mainly seems to mean crouching, but also fisheyes the lens. When you’re in stealth mode and concealed by shadow, the view also tints blue to let you know, highly reminiscent of the stealth view in the Penumbra games. (Penumbra came later, but don’t call it unoriginal. It put its own twists on the mechanic.)

The game is basically a first-person shooter with stealth elements. Or at least, the opportunity for stealth. My own experience is that stealth generally works here like it does in Dungeons & Dragons: it usually ends in a big fight with all the guards, because that’s so much easier to pull off successfully. There’s an explicit “stealth mode”, which mainly seems to mean crouching, but also fisheyes the lens. When you’re in stealth mode and concealed by shadow, the view also tints blue to let you know, highly reminiscent of the stealth view in the Penumbra games. (Penumbra came later, but don’t call it unoriginal. It put its own twists on the mechanic.)

Despite being primarily a first-person game, there are moments when it switches to third-person view, the better to show off Vin Diesel’s manly frame as he climbs up a stack of crates or twists a valve handle. But even when you’re in first-person mode, this is one of those few games where you can look down and see your body (or at least your legs), just like in Mirror’s Edge. The system also shares in Mirror’s Edge‘s problems (or design decisions) with disorientating the player. Fight sequences are turbulent. If it’s a hand-to-hand fight — which it very often is, given how hard it is for prisoners to get their hands on firearms — your viewpoint gets thrown around a lot, even when you’re hitting the other guy rather than getting hit yourself. (Sometimes I’ll be unsure about who actually hit whom.) If it’s a gunfight, the guards’ guns are powerful enough to knock you back, and they all have built-in flashlights that can blind you to your surroundings, particularly when the surroundings are dark.

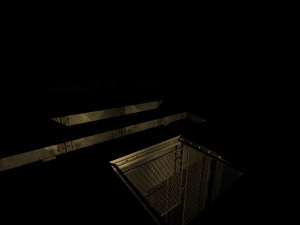

But then, darkness isn’t supposed to be a problem for Riddick, is it? Night vision — “eyeshine”, as the game terms it — is one of his core characteristics. It’s the reason he was so crucial to everyone’s survival in Pitch Black. It’s why he wears those goggles all the time: without them, daylight is like looking into the sun. Well, you don’t start the game with eyeshine, but you acquire it partway through, right after a harrowing sequence of darkness-based scenarios — first a failing flashlight battery, then a limited supply of flares, twisted troglodytes attacking you all the while — that serves both to make you grateful to not have to deal with darkness any more and to use up the designers’ ideas for darkness-based scenarios while they’re still an option.

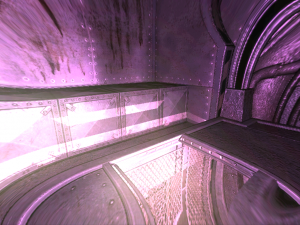

But then, darkness isn’t supposed to be a problem for Riddick, is it? Night vision — “eyeshine”, as the game terms it — is one of his core characteristics. It’s the reason he was so crucial to everyone’s survival in Pitch Black. It’s why he wears those goggles all the time: without them, daylight is like looking into the sun. Well, you don’t start the game with eyeshine, but you acquire it partway through, right after a harrowing sequence of darkness-based scenarios — first a failing flashlight battery, then a limited supply of flares, twisted troglodytes attacking you all the while — that serves both to make you grateful to not have to deal with darkness any more and to use up the designers’ ideas for darkness-based scenarios while they’re still an option.  Once you have eyeshine, you can toggle it on and off at the touch of a button, which presumably flips the goggles on and off. When active, it gives the entire screen a nice pinkish irridescence and warping, one of the better nonhuman-vision effects I’ve seen. And yes, if you activate it in normal lighting, it washes out the screen with impenetrable white.

Once you have eyeshine, you can toggle it on and off at the touch of a button, which presumably flips the goggles on and off. When active, it gives the entire screen a nice pinkish irridescence and warping, one of the better nonhuman-vision effects I’ve seen. And yes, if you activate it in normal lighting, it washes out the screen with impenetrable white.

Eyeshine resolves one of the basic dilemmas of stealth games. In the Thief series, and games on a similar model, darkness is safety. Thus, you want to make as much darkness as you can. But this makes it impossible to see where you are or what you’re doing, so there’s a tension there: you want the environment to be dark enough that the guards can’t see you, but not so dark that you can’t see them. But with Riddick, that tension completely goes away. Darkness has no downside. Accordingly, the game limits your access to it. There are areas open to the sky, where you can’t shut off the sun. More often, there are overhead light fixtures, out of reach. The only way I’ve found to put them out is to shoot them out, and the sound of a gunshot alerts the guards, ruining any chance you had for a stealth kill. But if they’re already shooting at you, plunging your immediate area into darkness definitely makes it harder for them. The only problem, then, is those flashlights on their guns, which blind you even more effectively when the goggles are off.

The most strange-feeling part of the various views is being temporarily ejected from them. As I mentioned, actions such as climbing switch you to a third-person camera. Since this isn’t seen through Riddick’s eyes, it doesn’t get the stealth or eyeshine effects. At the very least, you’re suddenly switching from blue or pink back to the game’s usual FPS browns and greys. Worse, maybe you’ve shot out all the lights, and suddenly you can’t see anything at all.

Comments(2)

Comments(2)

Well, Starbreeze Studios, developer of this game are old demoscene people, creators of Fast Tracker II if I recall correctly, so your tech-demo impression isn’t that far-fetched.

It’s been a while since I played the game, but I seem to remember making heavy use of a stun gun to shoot out the lights: maybe one carried by guards. Either it was quieter or had infinite ammo, and it was my primary ranged weapon for much of the game.