The Half-Life games have a reputation as the thinking person’s gorefest. They focus more on environmental puzzles than the typical FPS. They pander to the intellectual mystique by giving us a bearded, bespectacled action hero with a PhD in theoretical physics. But mainly, the original was one of the first games of its genre to try to tell a compelling story, and to do it entirely through the FPS medium rather than through cutscenes or journal entries.

The Half-Life games have a reputation as the thinking person’s gorefest. They focus more on environmental puzzles than the typical FPS. They pander to the intellectual mystique by giving us a bearded, bespectacled action hero with a PhD in theoretical physics. But mainly, the original was one of the first games of its genre to try to tell a compelling story, and to do it entirely through the FPS medium rather than through cutscenes or journal entries.

The story told wasn’t just a simplistic good-vs-evil one, or even morally-questionable-vs-evil (as seems to be fashionable in the more violent games these days), but one of confusion, of terrible things happening without anyone wanting them. One of the more effective plot elements is the re-evaluation of the soldiers. At first, the PC’s colleagues believe that soldiers are coming to rescue them from the monsters they’ve inadvertently unleashed, but it turns out that their orders are to contain the incident by killing everything on the site, scientists included. The soldiers are initially depicted as brutes who enjoy murdering unarmed civilians — “I killed twelve dumb-ass scientists and not one of ’em fought back. This sucks.” — which justifies in the player’s mind anything you do to them in return. But later, you overhear other soldiers talking about Gordon Freeman, the player character, who’s been declared enemy #1 at that point. One of them says “All I know for sure is he’s been killing my buddies”, humanizing their side of the struggle. The climax of this part of the story is when you overhear a commander declaring in no uncertain terms that he disagrees with the orders. If that had happened earlier, there could have been reconciliation, but it’s too late. When he sees you, he will recognize you as the person who’s been killing his men. He’ll try to kill you to prevent you from killing him, which means you have to kill him to prevent him from killing you. You have to wonder how many real-world conflicts play out the same way, fear of violence making it a certainty.

Half-Life 2 also has masked soldiers, the “CP” (opposite of the PC?), first shown abusing the citizens of the dystopian city where the game starts. If the player is ever given reason to sympathize with them, I have yet to reach that point. OK, there is a scene at a recruitment office, where an applicant tells you that, although he doesn’t like the CP, he’s decided to join them because it beats starving to death on the street. But that’s been it so far. The game has, however, been rehabilitating the monsters. One of the most common monsters from Half-Life was the Vortigaunts, very-rougly-humanoid aliens that can shoot energy beams. In Half-Life 2, a number of them have learned English and joined the human resistance, and provide you with lots of assistance, making me feel guilty for having killed so many of them back in the first game. And one of the things that the Vortigaunts give you is the means to tame the bugs.

The game calls them “antlions”, even though that name is already taken. They’re roughly the size of large dogs, and they burrow under the sand, emerging to attack anything that walks on it, endlessly spawning more to replace those killed. One of the more interesting bits of gameplay is a sandy area with scattered rocks, where you can move safely as long as you stay on the rocks. If you slip, bugs come, and you have to get back on the rocks before you can kill them all, but their attacks tend to push you off.

Now, the bugs aren’t the sort of thing that can say “All I know for sure is he’s killing my buddies”. They’re dangerous animals, nothing more. Once you have a Pheropod, though, they’ll never hurt you: they’ll just follow you around, unless you throw the Pheropod at something, in which case they’ll rush over there and attack whatever they find. You can use this to fight battles without putting yourself at risk, crouching behind cover while your chitinous minions do all the work and get slaughtered in great numbers for your benefit. (This is another way that it’s a thinking person’s game: scenes that reward tactial thought more than quick reflexes. It’s the polar opposite of Serious Sam.)

There’s some uneasiness about this kind of fighting, though, because you’re basically using monsters to attack humans. In fact, you’re using them only against humans, as it’s established pretty early that the bugs are no good at all against monsters. Back in the first Half-Life, it was whispered among the soldiers that Freeman was responsible for the whole emergency — that he had deliberately summoned the monsters. While it’s true that he had a hand in the experiment that created the rifts between Earth and Xen, there was nothing deliberate about it. But now, in the sequel, you really are summoning alien monsters and setting them on your enemies. I really hope that the CP is making video recordings of these fights, because there’s some priceless anti-resistance propaganda to be made from this.

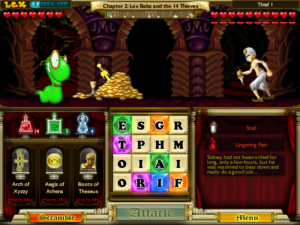

Bookworm Adventures is a pretty short game. It has three chapters (themed on Greek mythology, Arabian Nights stories, and classic horror — all it needs is a generic fantasy/fairy tale chapter and an African chapter and it would be the Quest for Glory series). I completed one chapter per session. I’m not sure how to feel about this. On the one hand, I’m not a fan of padding games out unnecessarily. This game demonstrates all of the special attributes monsters can have — attack side-effects, defensive powers, vulnerabilities to particular categories of word — and once the game is out of new tricks, it doesn’t overstay its welcome. On the other hand, padding things out is largely what RPGs do. It somehow seems wrong to keep it short.

Bookworm Adventures is a pretty short game. It has three chapters (themed on Greek mythology, Arabian Nights stories, and classic horror — all it needs is a generic fantasy/fairy tale chapter and an African chapter and it would be the Quest for Glory series). I completed one chapter per session. I’m not sure how to feel about this. On the one hand, I’m not a fan of padding games out unnecessarily. This game demonstrates all of the special attributes monsters can have — attack side-effects, defensive powers, vulnerabilities to particular categories of word — and once the game is out of new tricks, it doesn’t overstay its welcome. On the other hand, padding things out is largely what RPGs do. It somehow seems wrong to keep it short. Comments(2)

Comments(2)